Indian architecture, a testament to the subcontinent’s dynamic cultural history and diversity, has evolved through millennia, influenced by its rich heritage, geography, religious beliefs, and cross-cultural exchanges. From ancient cave temples and monumental rock-cut sculptures to modern skyscrapers, Indian architecture captures the essence of each era, creating a timeline of creative expression and technological prowess. Let’s embark on an exploration of Indian architecture’s salient features, journeying from ancient times to contemporary innovation.

Ancient Indian Architecture

The roots of Indian architecture lie in its ancient civilization, beginning with the Indus Valley civilization around 3300 BCE. The remnants of this civilization, particularly in Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, reveal early urban planning and construction techniques. These cities featured well-planned streets, standardized brick sizes, and sophisticated drainage systems. This architectural precision reflects an advanced understanding of urban design and civic amenities, providing a strong foundation for the architectural wonders that followed.

In the Vedic period, architecture was primarily religious, with wood and thatch structures used for sacrificial rituals. The emphasis was more on functional spaces rather than grand designs. However, it was during the Mauryan Empire (4th–2nd century BCE) that Indian architecture began to develop its monumental character. The use of stone emerged, as evidenced by the pillars of Emperor Ashoka, which display intricate carvings and inscriptions of Buddhist edicts. The Sarnath Lion Capital, for instance, became India’s national emblem, symbolizing the art and architectural prowess of this period.

Buddhist and Rock-Cut Architecture

The advent of Buddhism marked a significant evolution in Indian architecture, as it introduced rock-cut caves and stupas. The rock-cut caves of Ajanta, Ellora, and Karla exemplify this architectural style, with intricately carved interiors that depict Buddhist stories and deities. These caves served as monastic complexes, featuring prayer halls (chaityas) and living quarters (viharas). The stupa, a dome-shaped structure containing relics, became a central architectural feature of Buddhism. The Great Stupa at Sanchi, built during the Maurya and Shunga dynasties, is a masterpiece of symmetry, adorned with gateways that narrate the life of Buddha through exquisite carvings.

Rock-cut architecture also found expression in the Deccan region, particularly during the Gupta period. These rock-hewn temples, such as the Udayagiri caves, are characterized by elaborate sculptures that display the growing influence of Hindu iconography. The development of temple architecture in this period introduced the shikhara (spire) as a prominent feature, symbolizing the link between the earthly and the divine.

Hindu Temple Architecture: Nagara, Dravidian, and Vesara Styles

Hindu temple architecture reached its zenith between the 6th and 13th centuries, marked by regional variations across India. The Nagara style dominated northern India, featuring temples with a curvilinear tower (shikhara) and a sanctum (garbhagriha) that housed the deity. Temples like the Kandariya Mahadeva in Khajuraho and the Sun Temple in Modhera exemplify the Nagara style, characterized by intricate carvings and a stepped arrangement of structures that create a towering, rhythmic form.

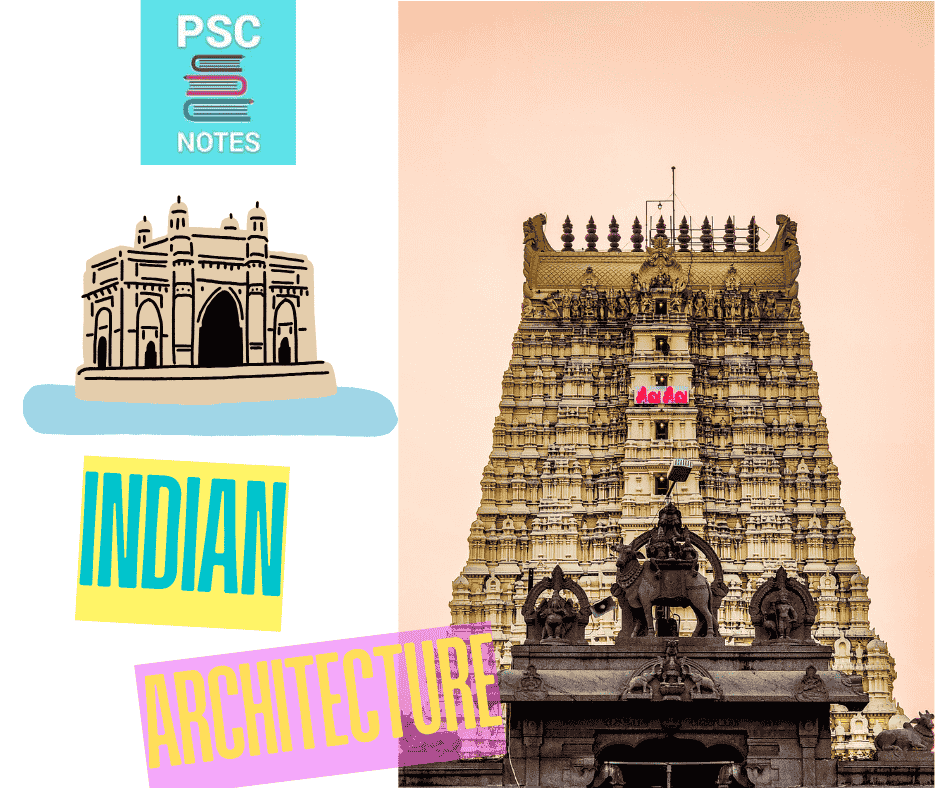

In the south, the Dravidian style flourished, marked by towering gateways (gopurams) and pyramid-like vimanas. The temples at Mamallapuram and the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur, built by the Cholas, are iconic Dravidian temples. Their architectural layout includes multiple enclosures, with each layer becoming progressively sacred as one moves closer to the garbhagriha. The emphasis on symmetry and the use of massive pillars with mythological carvings create an awe-inspiring effect, showcasing the architectural ambition of the Tamil kings.

The Vesara style, a synthesis of Nagara and Dravidian forms, emerged in the Deccan region, particularly under the Chalukyas and Hoysalas. The Hoysaleswara Temple in Halebidu and the Chennakesava Temple in Belur represent the Vesara style, featuring intricate sculptures that cover every inch of the temple walls. The Hoysala temples are known for their star-shaped plan and the elaborate carvings that depict scenes from Hindu epics, a testament to the artistry and craftsmanship of this era.

Islamic Architecture in India

With the arrival of Islamic rulers in the 12th century, Indian architecture began to blend with Persian and Central Asian influences. The fusion of Hindu and Islamic styles created a unique Indo-Islamic architectural tradition that shaped India’s skyline for centuries. This period saw the introduction of new elements like domes, minarets, arches, and intricate calligraphy.

The Delhi Sultanate era (13th–15th centuries) marked the beginning of monumental Islamic architecture in India. The Qutub Minar, a towering minaret built by Qutb-ud-din Aibak and his successors, stands as an enduring symbol of Indo-Islamic architecture. Other notable structures from this period include the Alai Darwaza, the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque, and the tombs of various sultans, which feature geometrically aligned layouts and exquisite stonework.

The Mughal period (16th–18th centuries) is considered the golden age of Indo-Islamic architecture, with its distinctive blend of Persian, Islamic, and Indian elements. Mughal architecture is characterized by symmetrical gardens (charbagh), marble inlay work, and elaborate ornamentation. The Taj Mahal, commissioned by Emperor Shah Jahan, epitomizes the Mughal style with its harmonious proportions, white marble surfaces, and pietra dura inlay work. Other iconic Mughal structures include the Red Fort, Jama Masjid, and Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, which embody the grandeur and sophistication of this architectural tradition.

Regional Styles and Vernacular Architecture

Alongside monumental architecture, India developed a rich tradition of vernacular architecture that reflected local materials, climate, and cultural practices. In Rajasthan, the stepwells (baolis) and forts like Mehrangarh and Amer Fort were built to withstand the harsh desert climate. The use of sandstone and marble, combined with intricate jali (lattice) work, allowed for ventilation and shade, essential for the arid climate.

In Kerala, the traditional tharavadu houses feature sloping roofs and courtyards designed to manage heavy monsoon rains. The bamboo and wood construction ensures durability, while the open design promotes airflow. Similarly, the bamboo houses of Assam and the bhunga houses in Gujarat’s Kutch region demonstrate how regional architecture adapted to environmental needs, using locally available materials to create sustainable, climate-responsive designs.

Colonial Influence on Indian Architecture

The arrival of European colonial powers in the 16th century introduced new architectural styles to India, most notably the Baroque, Neo-Gothic, and Neoclassical styles. Portuguese, French, and British architectural influences can be seen in cities like Goa, Pondicherry, and Kolkata. The Portuguese introduced churches with Baroque and Rococo influences, as seen in the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Goa.

The British Raj (1858–1947) had the most profound impact on colonial architecture in India, combining European styles with indigenous elements. The Indo-Saracenic style emerged as a blend of Gothic, Mughal, and Dravidian forms, producing landmark structures like the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, the Madras High Court, and the Gateway of India in Mumbai. British architects also introduced public buildings, railway stations, and civic institutions designed with functional layouts and grand facades, symbolizing the power and authority of the British Empire.

Modern and Contemporary Indian Architecture

Post-independence India sought to establish its architectural identity, balancing tradition with modernization. The first phase of modern Indian architecture was driven by architects like Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, who were invited to design cities and institutions that reflected India’s aspirations for progress. Le Corbusier’s design of Chandigarh, with its grid layout, open spaces, and Brutalist style, symbolized a new India, focused on functionality and simplicity.

Indian architects like Charles Correa, Balkrishna Doshi, and Achyut Kanvinde played significant roles in shaping modern Indian architecture. Correa’s projects, such as the Gandhi Memorial Museum in Ahmedabad, emphasize a fusion of modernist design principles with Indian aesthetics. Doshi, known for his sustainable and community-centered approach, designed the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, a campus that integrates local materials with an open, expansive layout that encourages interaction.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Indian architecture began to reflect the trends of globalization, with an emphasis on skyscrapers, glass facades, and high-tech designs. Cities like Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Gurgaon became hubs of contemporary architecture, with high-rise buildings that utilized advanced construction technology. The Infosys headquarters in Bangalore and the Lotus Temple in Delhi illustrate the diversity of modern Indian architecture, with the former showcasing sleek corporate design and the latter drawing inspiration from traditional Indian symbols.

Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Architecture in India

In recent years, sustainability has emerged as a central theme in Indian architecture, as the nation grapples with rapid urbanization and environmental challenges. Green building techniques, energy-efficient designs, and climate-responsive architecture are becoming increasingly important. The CII-Sohrabji Godrej Green Business Centre in Hyderabad, certified as a green building, incorporates natural lighting, rainwater harvesting, and solar panels, setting a benchmark for sustainable architecture in India.

Many architects are also returning to vernacular architecture principles, using local materials and techniques to create eco-friendly buildings. Architect Laurie Baker’s low-cost housing projects in Kerala, for example, highlight the use of brick and mud, creating structures that are affordable, durable, and suitable for the local climate. Baker’s philosophy of “minimal impact, maximum effect” has inspired a new generation of architects committed to sustainable development.